UM features the world’s only hurricane simulator able to generate Category 5 hurricane-force winds, a model that will help researchers solve some of the mysteries of storms and impacts of sea-level rise.

The little beachfront house took quite a pounding. Towering swells crashed into its wooden stilts, while brutal winds, some exceeding 130 miles per hour, pummeled its outer walls, shaking the home so violently it looked as if it would topple at any second. But remarkably, it stood firm, at least on this day. Tomorrow, and the next day, it would endure much harsher conditions—spawned not by nature but with the flip of a switch.

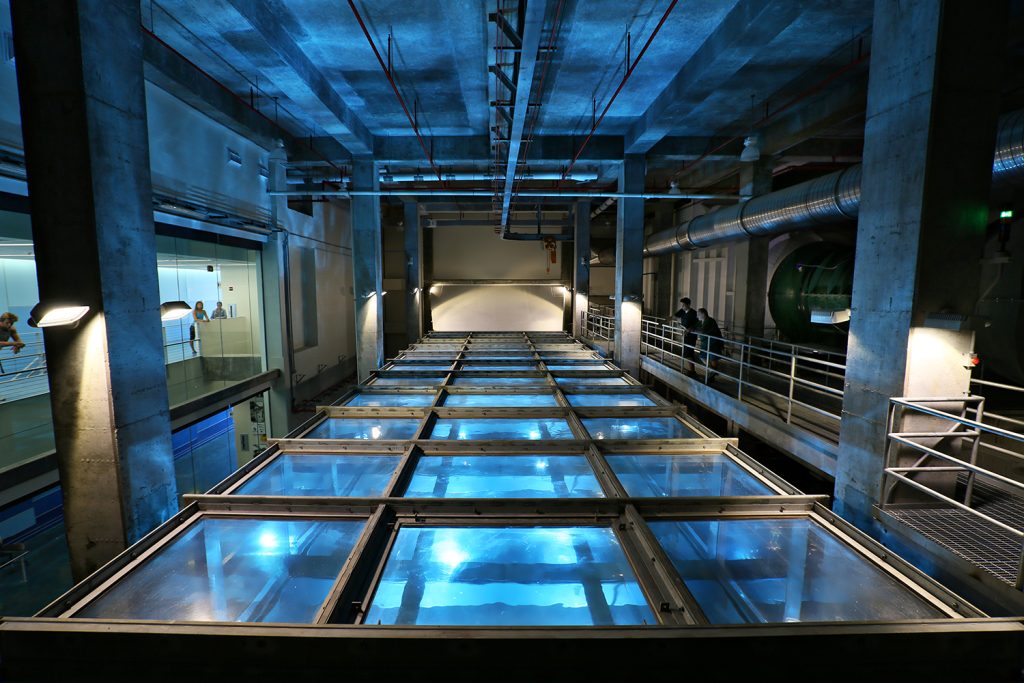

Tropical cyclones are a regular weather occurrence inside the University of Miami's new hurricane research facility, the Alfred C. Glassell, Jr. SUSTAIN (SUrge-STructure-Atmosphere INteraction) lab, where scientists can tinker with the controls of a 75-foot-long, 38,000-gallon wind-wave tank to simulate everything from a weak tropical storm to a cyclonic monster complete with 160-mile-per-hour winds, sea spray, and storm surge.

"There's no other facility like it in the world," says Brian Haus, professor of ocean sciences at UM's Rosenstiel School of Marine and Atmospheric Science, where the tank is located.

Haus, who co-wrote the grant proposal that helped UM obtain the federal stimulus money to build the tank, is not exaggerating. SUSTAIN, he explains, is unique because of its ability to generate Category 5 wind speeds (157 miles per hour or higher) over water.

About the Video

SUSTAIN is part of the Marine Technology and Life Sciences Seawater Complex on the Rosenstiel School campus.

Join the Conversation

Follow on Twitter:

Rosenstiel School, @UMiamiRSMAS

University

of Miami, @univmiami

UM

News, @univmiaminews

Marine Technology and Life Sciences Seawater Complex

Before SUSTAIN, that had never been done in a lab. A 1,400-horsepower fan, originally designed to ventilate mineshafts, makes it all possible, generating the powerful winds that travel across the seawater pumped into the tank.

By simulating and observing storm conditions in the tank, researchers hope to solve some of the mysteries of tropical cyclones that have puzzled meteorologists and forecasters ever since they started tracking them—such as why some storms intensify at an incredible rate.

The facility could also improve forecasting, says Mark DeMaria, chief of the Miami-based National Hurricane Center's (NHC) Technology and Science Branch.

"You can only go so far with theory," he says. "What you'd really like to do is get some actual observations. But it's difficult to put sensors in the middle of a major hurricane. The tank provides a way to simulate that process and actually take measurements of the fluxes to refine forecast models."

Because hurricanes often make landfall on shorelines with high-rise buildings, and with more and more of our coastal regions coming under the threat of rising sea levels caused by climate change, SUSTAIN is expected to play a major role in helping engineers and architects to design stronger and safer structures located near water.

Much like the scaled-down beachfront house that was placed in the tank, UM structural engineer Antonio Nanni, who studies how all kinds of structures perform under extreme conditions, has elaborate plans for SUSTAIN—from studying the effect of Category 5 wind speeds and massive storm surge on near-shore high rises, to analyzing what effect prolonged winds and waves have on sea-based oil rigs and bridges over bodies of water.

Nanni, the co-principal investigator of SUSTAIN, will also use his scale-model simulations to validate existing computer modeling.

"We have the ability now to conduct experiments we just couldn't do before," says Nanni, professor and chair of the Department of Civil, Architectural and Environmental Engineering and head of the College of Engineering's Structures and Materials Lab.

Often on the frontlines of hurricane and storm system tracking and warnings, NHC forecasters and scientists stand to benefit most from SUSTAIN's capabilities, using the data it produces to improve forecasting, which in turn will aid emergency management officials issuing hurricane evacuation orders.

Other researchers, some of them from overseas, have expressed interest in using SUSTAIN for testing, says Haus. Once they do, they will experiment with a high-tech wind-wave simulator unlike any other, one with 12 individual wave panels that can create almost any type of ocean environment—from multiple waves, long or short swells, waves that crash into each other, and even run in opposite directions.

"There's a million things we can do with this tank, and the longer we play with it, the more things we discover we can do with it," says Mike Rebozo, a senior technician at the Rosenstiel School who helps maintain the tank.

SUSTAIN is one part of the $45 million Marine Technology and Life Sciences Seawater Complex on the Rosenstiel School campus. The building's Marine Life Science Center is home to a National Institutes of Health-funded Aplysia lab, billed as the only facility in the world that cultures and raises sea hares for scientific research in aging, memory, and learning. Other research is being conducted on coral reefs and species such as toadfish and zebra fish in hopes that such investigations will improve human health.

The Glassell Family Foundation supported the construction of the wind-wave tank portion of the complex, but it was a $15 million stimulus grant from the National Institute of Standards and Technology that got the ball rolling on SUSTAIN, one of only a handful of proposals funded by the agency.

"We picked only the best of the best," said Mary Saunders, NIST associate director for management resources.

- Robert C. Jones Jr. / UM News