A new tool to measure air pollution levels in real time that is available online is being developed by a UM researcher.

Just as China's president, Xi Jingping, was set to join representatives of 195 other nations at the Paris climate talks in late 2015, air pollution and smog reached such dangerous levels in Beijing one day that authorities issued a rare "orange alert," prompting a halt in all construction and outdoor school activities and forcing the city's more than 22 million residents to stay indoors.

Meanwhile, in India, the air quality is no better. In fact, the average Indian citizen is exposed to more particulate matter—microscopic particles of dust, soot, smoke, and liquid droplets that can cause lung cancer and respiratory problems—than the average Chinese, a Greenpeace study found.

None of this is a surprise to Naresh Kumar, an associate professor of environmental health in the University of Miami's Miller School of Medicine's Department of Public Health Sciences. For the past 20 years he's studied air pollution and its effect on human health in developed and developing countries like China and India.

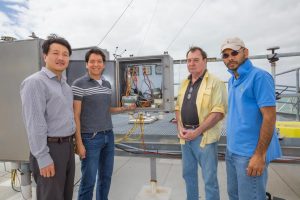

About the Photo

Naresh Kumar installed his air pollution monitoring device at the Rosenstiel School.

Join the Conversation

Follow on Twitter:

Miller School of Medicine,

@umiamimedicine

University of Miami, @univmiami

UM News, @univmiaminews

"Climate, without a doubt, has a detrimental impact on human health when there's air pollution," says Kumar. "Greater emissions from the combustion of fossil fuels in the presence of high temperatures and sunlight increase concentrations of ozone, an inflammatory gas. And that's been linked with asthma, stroke, and cardiopulmonary disease."

Almost a quarter of all disease is caused by environmental exposures that can be prevented. "While we have made great strides in characterizing personalized genotypes and phenotypes, we lack the ability to monitor personal environmental exposure," says Kumar.

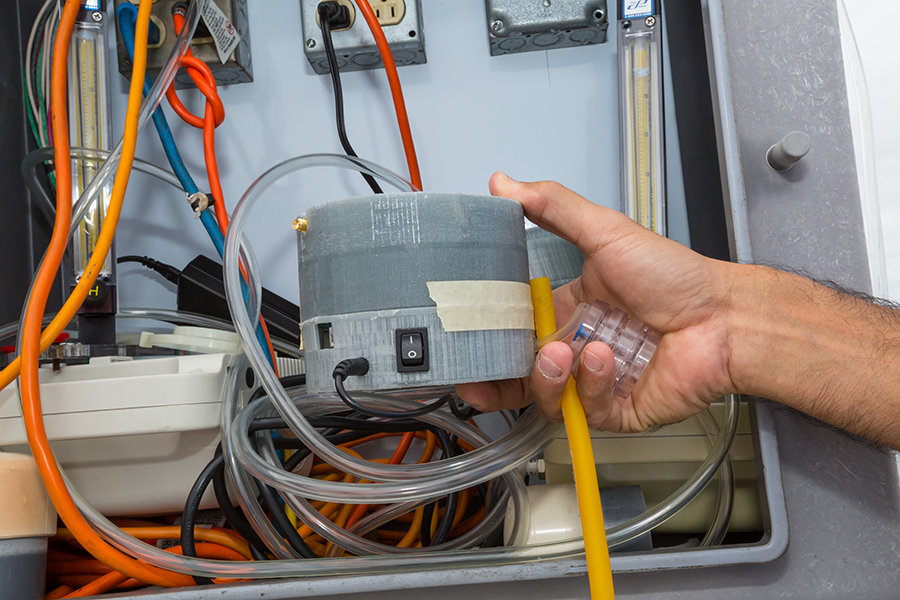

And that's precisely why Kumar, Sung Jin Kim, assistant professor of electrical and computer engineering in the College of Engineering, and colleagues developed UM PRECISE (Personal Real-time Environmental Exposure using Cellphone Integrated Sensors). Using multiple optical sensors, the device measures levels of particulate matter, records meteorological conditions, and uploads that data to the Internet via WiFi, giving researchers, health care professionals, and patients a way to monitor the acute effects of air pollution in real time.

"The objective," explains Kumar, "is to engage targeted patients in exposure avoidance and preventive behavior."

PRECISE has undergone three phases of testing, yielding promising results, and two of the sensors will soon be deployed on UM's Coral Gables and Virginia Key campuses.

Using satellite data and with the assistance of UM's Center for Computational Science, he also tracks air pollution rates in Delhi and posts the data on a website, which allows the public and policymakers to access daily air pollution estimates anywhere in and around Delhi.

Kumar is planning to launch similar websites that track air pollution rates in Cleveland, Ohio, where smog has become a major public health concern, and Texas, where fracking—a technique in which chemicals are injected deep underground to break up rocks surrounding oil and gas deposits—has led to serious concerns about the environment and health.

Kumar notes that while stringent legislation has helped to reduce air pollution in the U.S., health disorders such as asthma, allergies, and other respiratory disorders caused by poor air quality have not declined at the same pace, but have rather increased. The in-home use of aerosol cans and certain cleaning products are to blame, he says.

"Two out three homes in Miami have mold," says Kumar, "but there are no laws to regulate for that, except for occupational settings."

- Robert C. Jones Jr. / UM News