A UM professor is retooling engines to use methane gas from landfills, helping to reduce gas emissions harmful to the environment.

Michael Swain, B.S. ’71, M.S. ’73, Ph.D. ’79, spent years researching hydrogen as an alternative to gasoline for internal combustion engines. It burns clean, but it’s costly to produce.

“We have to develop engineering solutions that are profitable,” says Swain, associate professor in the College of Engineering's Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering.

“As I looked around for another fuel source, I found one that’s free—methane from landfills. Right now landfills have to pay to get rid of methane by flaring it. So for them, this is a profitable enterprise.”

The decomposition of organic materials in landfills produces greenhouse gases—methane and carbon dioxide. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, the global warming impact of methane is 25 times greater than carbon dioxide. Through its Landfill Methane Outreach Program (LMOP), the EPA has partnered with legislators, landfill operators, and other industry personnel to convert methane into energy at some 600 sites nationwide—and potentially hundreds more.

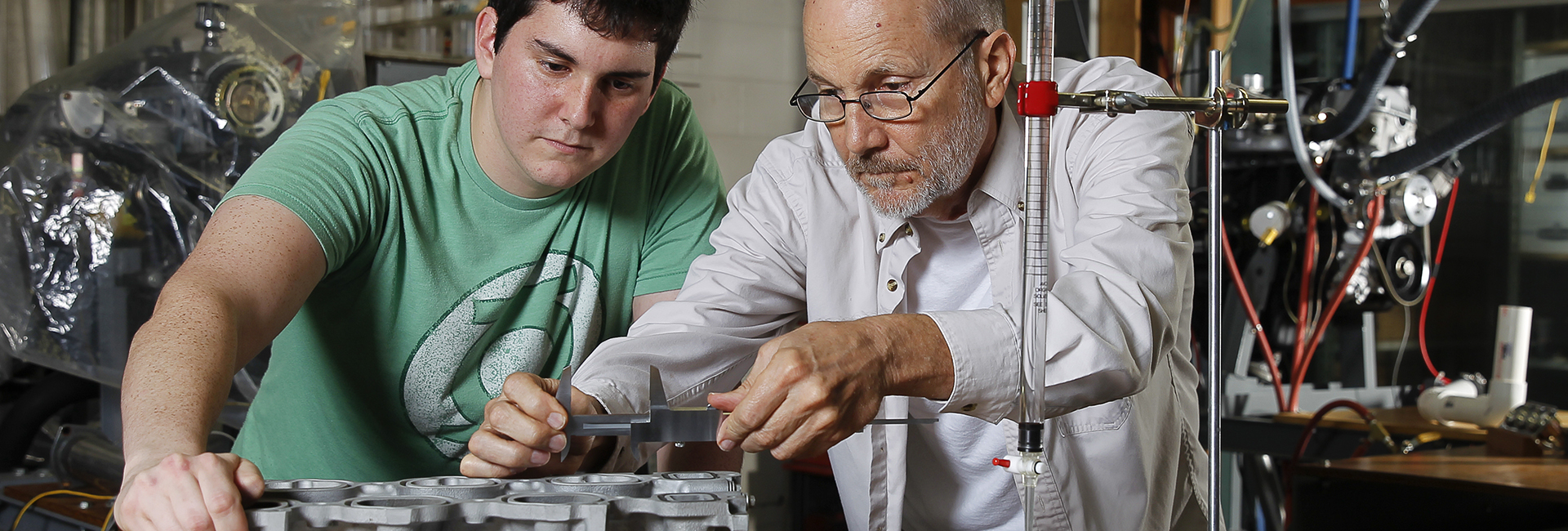

About the Photo

Michael Swain, right, associate professor in the Department of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, works with his student, Ricardo Palacios, on converting an engine to run on methane gas.

Join the Conversation

Follow on Twitter:

UM College of Engineering

Dean Bardet, @UMCoEDean

University of Miami, @univmiami

UM News, @univmiaminews

The EPA estimates that if all qualifying sites participated in LMOP, they could power more than half a million U.S. homes, in addition to generating energy to run landfill operations. Swain, an internal combustion engine specialist, thinks he and his collaborators can crank the power and number of sites even higher with a more efficient engine approach. One of his collaborators is his brother, Matthew Swain, who helps build engine prototypes at the Miami-based firm he owns, Analytical Technologies.

Most LMOP sites run their methane through large diesel engines, commonly produced by Caterpillar. Swain’s team purchases used automobile engines to produce Redesigned during Remanufacture (RDR) internal combustion engines modified for this purpose. He says that a bank of four RDR engines can yield more energy output than one larger, more expensive diesel generator.

Offering even more bang for the buck, Swain’s strategy recycles junkyard waste and creates job opportunities for auto mechanics who can service the engines. This summer Swain's team will be testing an RDR engine at a landfill in West Palm Beach, Florida.

How renewable is the plan? Organic garbage won’t be in short supply any time soon, and neither will the internal combustion engine, Swain says.

“Ford, General Motors, Porsche, Mercedes, Volvo, Jaguar, and Infiniti have all released new engine families within the last two years,” Swain says. “For example, Mercedes just spent $3 billion on its new engine family. Automakers don’t make that kind of investment unless they figure the engines will be around for the next 20 to 30 years.”

- Meredith Camel / UM News